In the final scene of A Court at Constantinople, barrister James Bingham asks Judge Edmund Hornby, “Did we do them justice?”

The question arises from what has happened to Rosamund Colborne, a British merchant’s daughter, and Osman Mehmed, a young Turkish law student. The query fuses two themes of the novel—British treatment of the Ottomans as “uncivilized” in matters of law and justice (focused on Mehmed’s character) and the discrimination and danger that girls and women confronted in “civilized” British society (centered on Rosamund’s character). I wanted these themes to be historically authentic, interconnected, and relevant to our world.

Both themes touch on very controversial historical and contemporary issues—imperialism and gender mistreatment. Put differently, pride and prejudice are not going to produce a happy ending. This post explores my attempt to craft a gender theme in the novel. A subsequent post will address the theme focused on the “standard of civilization” used by European countries in their relations with non-European peoples during the age of empire in the nineteenth century.

Best Laid Plans

As between them, I anticipated that the gender theme would be harder to render authentically, connect to the standard of civilization, and relate to contemporary concerns about gender issues. The empire theme has the “clash of civilizations” between the British and Ottomans—a context for which historical research would provide ample material. For the gender theme, my plan was to explore a “clash within” the British civilization concerning the treatment of girls and women—and then link this clash to other themes focused on the relationships between law, justice, and power.

Executing this plan encountered challenges, particularly how to weave the gender theme credibly into the story through the lives of the three main characters—Rosamund, Mehmed, and James Bingham, a young British barrister. Unexpectedly, diplomatic correspondence between the British Supreme Consular Court at Constantinople and the Foreign Office in London provided a way to achieve my ends.

A Disturbing, But Curious, Case

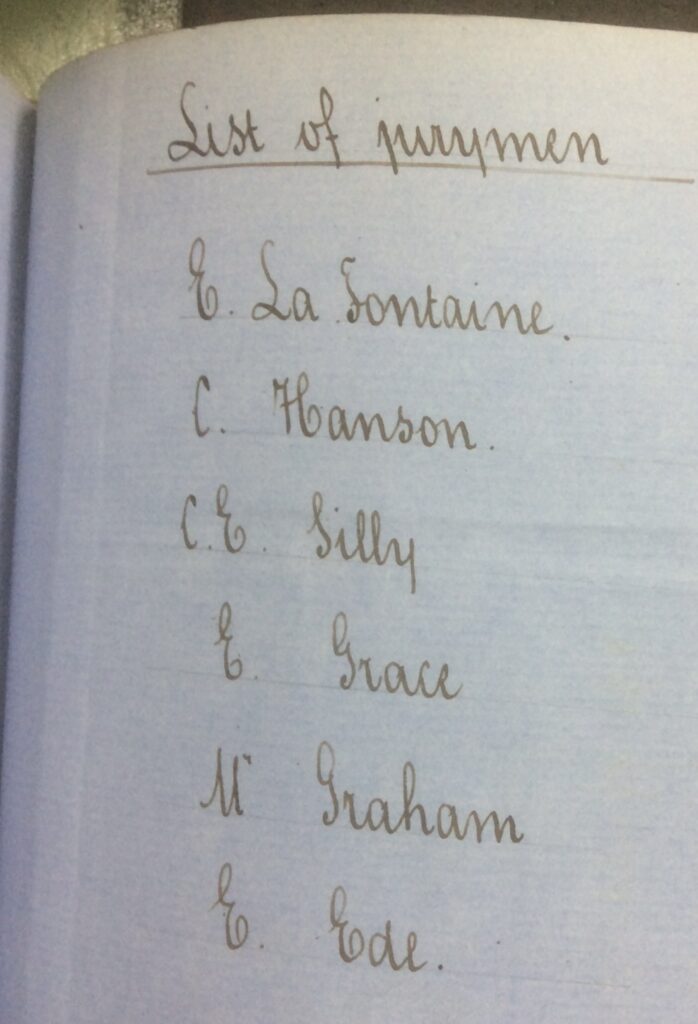

As anticipated, the diplomatic papers in the British National Archives recorded events and controversies about problems between the British and Ottoman governments, some of which I used to support the empire theme and other purposes in the novel. However, the diplomatic correspondence also contained documents from an 1859 criminal case, R v Sinclair, involving an alleged “indecent assault”—the language used in the case—of an eleven year-old girl, Susannah Hicocks, by a man, Thomas Sinclair.

These documents jumped out of the correspondence between the British court and the Foreign Office because the case only involved British subjects and English law rather than relations between the British and Ottoman empires. Further, in the archival materials that I reviewed, R v Sinclair was the only criminal case mentioned that came with a trial transcript and correspondence from the defendant’s family to the British Foreign Secretary.

Why did a case with no importance in British-Ottoman affairs create this unusual paper trail in diplomatic correspondence? The answer connects to concerns that British subjects had with how the British Supreme Consular Court exercised its powers over them. In that sense, R v Sinclair has a “domestic” rather than “diplomatic” feel to it. And, as such, it had me asking questions and imagining possibilities.

Did the case disturb those involved in, and affected by it, for reasons that might also upset people today? Could it be an authentic moment for historical fiction that might support major themes, help develop characters, catalyze the plot, and touch contemporary concerns about how legal and justice systems still struggle with gender issues, including sexual violence?

I decided, for better or worse, to use the case.

R v Sinclair in the Story

In Chapter 7 of the novel, R v Sinclair becomes the basis for the first of three interconnected trials and courtroom dramas. It provides the moment in the plot where earlier threads concerning gender mistreatment come together and when the lives of the main characters really begin to intertwine in ways that shape the rest of the story.

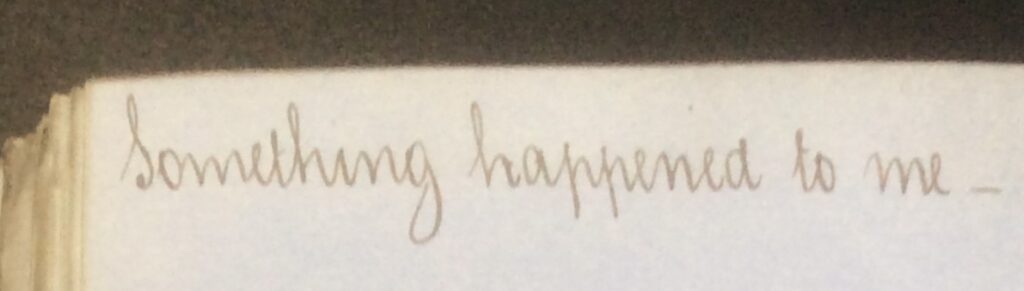

In my rendering, Queen’s Counsel for the Crown tells the jury that the case is disturbing for many reasons, including that the alleged victim, a child, must testify in the interests of justice.

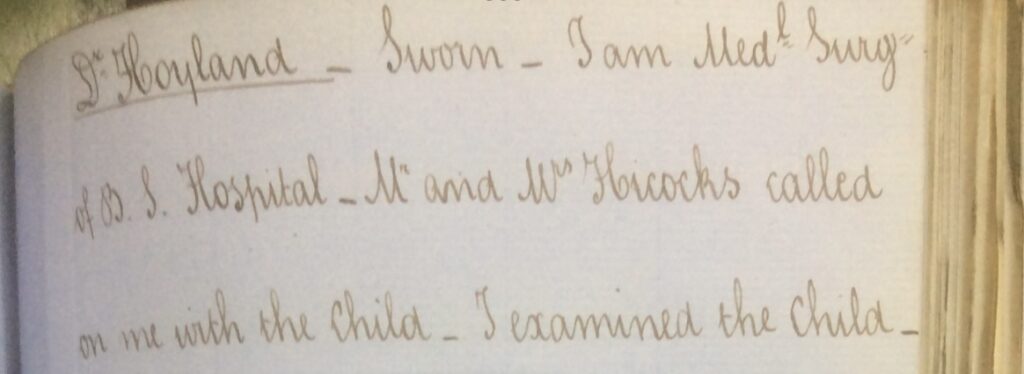

As emotional reactions from those watching the proceedings indicate, testimony—based on the trial transcript in the archive—from Susannah and Dr. Charles Hoyland, the physician who examined her after the alleged assault, make for a very uncomfortable experience.

Medical Surgeon of the British Seamen’s Hospital, Constantinople (1859).

Then Queen’s Counsel for the defense compounds the unpleasantness by challenging the veracity of the females making the allegation—a phenomenon often seen in contemporary court proceedings involving accusations of gender violence against men.

The case disturbs James, Mehmed, and Rosamund—not only because of the crime but also because it affects them personally. The reasons for Mehmed’s reaction appear in Chapter 2 and concern equally, if not more, disturbing gender violence. Chapter 5 begins with James’ memories of domestic violence during his childhood. Chapter 5 ends with James seeing “his mother at the kitchen table,” Mehmed remembering his “sister’s shame,” and both shaken by what Mrs. Hicocks’ claimed happened to her daughter. Mother, sister, daughter—the theme concerning gender mistreatment is developing before R v Sinclair happens.

Rosamund’s anger about how women are treated in British society is on display in Chapter 4 and features again in Chapter 6. During R v Sinclair, she rips into James and the other “heartless men” who cannot see the defendant’s guilt, denounces the prejudiced British legal system, and marvels at Susannah’s courage.

In addition to being excoriated by Rosamund, James is unsettled during the trial because he has never been involved in such a case. In contrast to Rosamund’s clarity about it, he does not know how justice can be done when—in the absence of meaningful evidence—the trial essentially pits the allegation of a girl and her mother against the denial of the man accused.

The verdict by the jury of six men has serious ramifications for all the main characters, but especially Rosamund.

Importantly, R v Sinclair, and what happened to Susannah, does not disappear as the tale continues. The next two courtroom dramas feature testimony from Rosamund that directly connects to that first traumatic trial. In the second trial, Rosamund uses language uttered by Susannah in R v Sinclair. The third trial features Rosamund seated in front the witness box—just as Susannah had been—struggling with what has happened to her, the attempts by Queen’s Counsel for the defense to impugn her behavior, and whether she should, like Susannah, have the courage “not to stay silent.” And, like R v Sinclair, the ways in which these trials end have profound consequences for the story.

Thematic Connections

R v Sinclair, and its thematic role in the novel, also provides a counterpoint to the British application of the “standard of civilization” against the Ottomans. Under this standard, the British are “civilized,” but, as a character in Chapter 1 notes, British women upon marriage became something akin to the husband’s property. Women who refuse this fate are, as Rosamund’s anger and predicament show, vulnerable to male power. The Ottomans hate being treated as “uncivilized,” but Mehmed’s teacher, Hasan, identifies violence against girls (also based on a primary source) to force his students to see problems with Ottoman behavior that cannot be blamed on the British. The “standard of civilization” no longer exists in international law. The same cannot be said of misogyny, discrimination, and violence against girls and women in societies around the world.

Rosamund’s anger about the treatment of women in British society, and Mehmed’s fury at being considered “uncivilized” by the British government, have parallels. Russia’s invasion of Ottoman domains, and the subsequent Crimean war, wrecked Mehmed’s childhood and brought the European powers, especially the British, deeply into his young adult life. He is unhappy with how British power denigrates his beliefs and dictates his future. His resistance to British influence gets him into trouble with the British and Ottoman governments. Like Rosamund, he feels trapped, and he searches for “another way” between British and Ottoman injustice. In one of the novel’s more symbolic moments, Mehmed crafts his vision for Ottoman justice inside a British gaol cell. What he endures creates connections with Rosamund that are important as the tale unfolds.

Did I Do Them Justice?

In that final scene of the novel, Judge Hornby does not answer James’ question, which is left hanging between them. It is, of course, a question also directed at the reader as the story ends—and at me, the author of the tale.

Did I do justice to the gender theme, the reasons I had for using it in the novel, the case of R v Sinclair, and Susannah? My motivation for writing this post might, in some sense, arise from fear that I did not succeed. Perhaps that fear will provide incentive for me to ponder more deeply whether there was “another way” to achieve what I had intended.