A few years back, I lived in an old Illinois town on the banks of the Mississippi River. Stories and tall tales about famous people visiting the town seemed everywhere. Abraham Lincoln once took libations in the living room of this house. During his steamboat days, Samuel Clemens slept in that barn. But the most intriguing stories were the ones that could not be told.

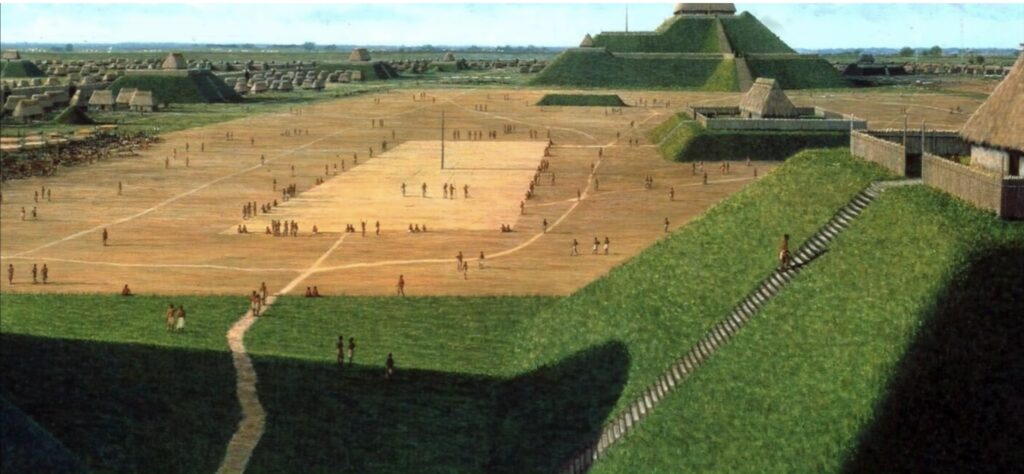

Not far from my river town stood Cahokia Mounds, one of the most important pre-Columbian archeological sites in the United States. Once upon a time, a large city thrived there, dominated by a massive earthen platform (today called Monks Mound) on which the leaders of a complex society probably lived. Archeologists have made discoveries, but Cahokia and its people remain shrouded in mystery. We do not know why, for example, the city was abandoned hundreds of years before Europeans arrived in North America.

Source: Cahokia Mounds Museum Society

In his new novel, Francis Spufford makes Cahokia the epicenter of a story unfolding within an alternative history of the United States in which native Americans exercise power. Set in the 1920s, Cahokia Jazz starts as crime noir fiction, with Detective Joe Barrow as main character, before it peels back the economic, political, and spiritual layers of the native American people who control Cahokia, both the city and the state that forms part of the United States. But Barrow’s journey into the heart and soul of Cahokia proves as dark and tragic as the brutal crime that begins the story.

Crime and Punishment

The novel covers a week in the life of Barrow, who the reader meets as he responds to a gruesome crime with his partner, Phin Drummond. Their relationship began when they met as soldiers during World War I. Barrow is mixed race, part black and part native American. Drummond is white, but friendship developed because Drummond treated Barrow as a person and not a brown “mongrel.”

As detectives, Drummond is the brains, and Barrow—a huge, powerful man—is the brawn. But Barrow is also a talented jazz pianist, a passion that gives his character depth and possibilities that become important as the story unfolds.

Spufford uses the bond between Barrow and Drummond, and Barrow’s musical soul, to set up the deteriorating race relations in Cahokia among native Americans and whites, with—interestingly—blacks on the margins of that simmering racial strife. At first, the crime that Drummond and Barrow investigate appears to involve a ritualistic murder of white man by a native American. But, as the investigation proceeds, the murder appears staged to provide whites, led by the Ku Klux Klan, with a pretext for overthrowing native control of the city and state of Cahokia.

That shift in the perpetrator and purpose of the crime adversely affects the relationship between Barrow and Drummond, leaving Barrow more on his own to pursue the truth. That pursuit takes him deep into the political and cultural realms of the native Americans in Cahokia, especially the royal House of Hashi led by the Man of the Sun, Sebastian Hashi, and his niece the Moon, Couma Hashi.

Barrow becomes entwined in the machinations of the House of Hashi as it seeks to protect the people it serves from impending violence by the Klan. But Barrow is disturbed by not only the Klan’s racism—and who facilitates it—but also the ruthless ways the House of Hashi wields power. As his world darkens, Barrow finds solace and freedom in music and must decide whether to remain in Cahokia or leave to play jazz with a traveling band of black musicians. Spufford brings the threads of the story together in an ending of sex, betrayal, and sacrifice that is noir to the bone.

Reimagining Cahokia

The premise of Spufford’s alternative history of the United States is that European diseases did not decimate native American populations and render the North American continent’s indigenous peoples vulnerable to the encroaching power and prejudice of European empires and, later, the United States. But, in Spufford’s reimagining of history, the native populations learned to exercise political and military power on an equal footing with whites.

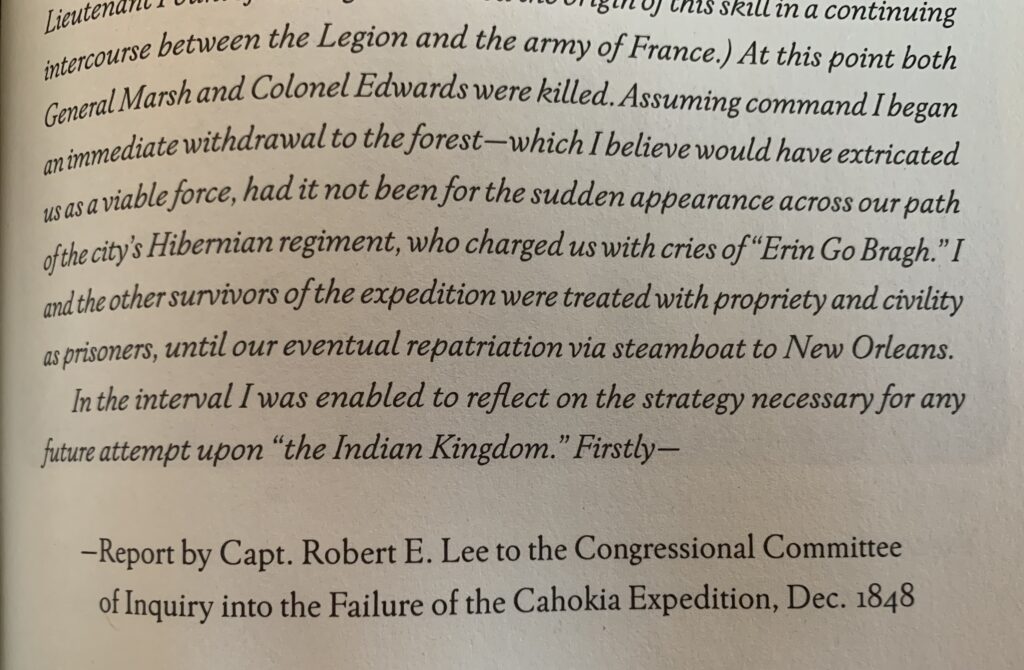

For example, in sprinkling the novel with “historical documents,” Spufford includes a report from a then-Captain Robert E. Lee, whose attempt to invade Cahokia in 1848 was defeated, with Lee being taken prisoner in the battle. Similarly, Spufford has a Cahokian general—not General Ulysses S. Grant—capture Vicksburg, Mississippi, for the Union during the Civil War. In the story, the Klan experiences the military prowess of Cahokia when it attempts to overthrow the House of Hashi.

Spufford’s creativity also shines in his crafting of the cultural and spiritual aspects of Cahokian society. Cahokians blend Catholicism with traditional religious practices in ways that put them in equipoise between white Christians and indigenous beliefs.

The mixed religious system exists as much for political as spiritual reasons, reflecting another way the author fleshed out how his Cahokians survived not only European diseases but also the violent dispossession and relentless discrimination that indigenous peoples experienced across the American continent.

And, as Barrow painfully discovers on his journey, the Cahokian relationship to power and piety accepted—as did Cahokia’s enemies—that the ends justify the means: “But he’d seen something else, too, and couldn’t unsee it—that there was a kind of dreadful symmetry in what these powers would do, would wink at, would permit, for the sake of victory.”

The Streets of Cahokia City

Alternative histories often leave a gap between flights of imagination and the fates of the characters in that made-up reality. Spufford avoids that problem by, first, anchoring the story in genre of crime noir, which keeps characters grounded in the grit and grind of urban life.

Second, Spufford goes to great lengths making the city of Cahokia real, with a map and details and descriptions about its diverse neighborhoods and streets. That material makes the imaginary city more familiar and accessible, which, in turn, helps accentuate how urban life in a place run by native Americans could still be different. The author underscores those effects when he describes St. Louis as a puny, backwater town on the Mississippi, while Cahokia is the big, modern city. Cahokia is St. Louis, except that it is not.

Having lived on the banks of the Mississippi, I have experienced the great river in flow and flood. Those memories made me appreciate how Spufford connected the river to his Cahokia and those living in it. I found the following passage particularly evocative, as well as a gem reflecting Spufford’s skill as a writer:

Out in the thick gray a half-hour later with a belly full of scrambled eggs, he [Barrow] could tell with every step that the fog was the river’s creature. It had the river’s smell, the organic smell of growth and rot together, still chilled by the winter but waking up. The human contribution was there too. A Cahokia fog always had smoke in it, and gas fumes, and cooking grease: but they were subdued, pushed back to a minor place in the chord. From out of the cold brown levels of the water as it slid south, creasing and tilting, dimpling against the great caissons of the Bridge, a billion billion droplets had risen, breathed by the river into the air. Each one a messenger of the ceaselessly moving silt below, in which was digesting everything that ever fell into it on its path down the continent, from dead trees to dead people. And now the exhalation of all this filled the streets with dense, soft vapor that behaved like a live thing itself, stirring slightly at the passage of the bodies through it, hugging walls, licking at doors and windows with damp particulate tongues.

Cahokia Silence

Spufford’s novel has me keen to visit Cahokia again, perhaps with a copy of his map, to picture his creative, provocative alternative history from the summit of the great earthen platform. But I know from previous visits that, upon ascending to that vantage point, I can see, if not obscured by fog from the Mississippi, the sprawling metropolis of St. Louis. Where detectives work. Where power tempts. Where jazz plays. That vista brings home that Cahokia remains, and will forever be, lost in its silence.

Source: Anthony Earth