In working on my historical fiction novel, A Court at Constantinople, I planned a research trip to Istanbul in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic forced me to cancel it. The need to finish the book meant that I did not visit Istanbul before publishing it in 2023. That decision left me wondering whether experiencing Istanbul would have changed how I wrote the novel.

In September 2025, I finally traveled to that famous city. My explorations included visiting places that I used in telling the story and developing the characters.

at the Dolmabahçe Palace

To my surprise, the experience produced no regrets about the decision to publish before walking the streets of Istanbul, sailing on the Bosphorus, or crossing the Golden Horn. Instead, the trip repeatedly brought back the reasons why I wrote the novel. That realization does not, of course, improve the book. But going into the legendary city was meaningful because it made more real the challenges that using history in fiction creates.

Down Memory Lane

Stand anywhere in Istanbul and before, above, and below you are reminders of a place that has linked the Asian and European continents for millennia. The city is overwhelming historically. In bouncing from Greek Byzantium to Roman Constantinople to Ottoman Istanbul, I attempted to stop, however briefly, to see buildings and glimpse locations where characters in my novel, set in 1859, came and went as the story unfolded.

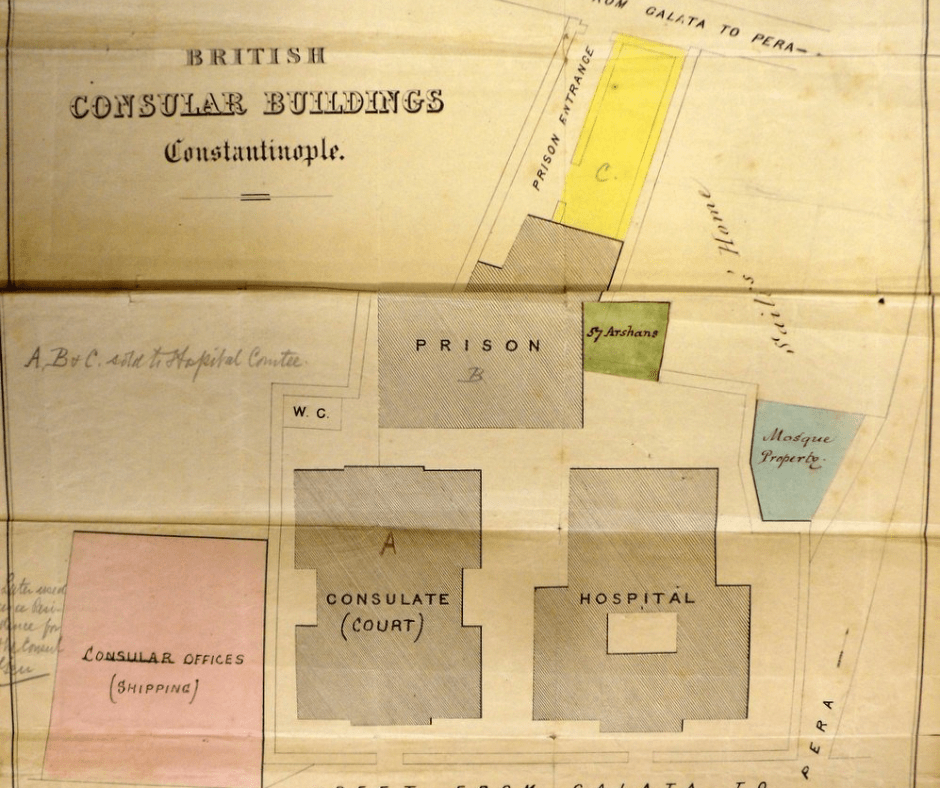

As expected, some places in the novel no longer exist, including the British Supreme Consular Court in the Pera district, Chief Judge Edmund Hornby’s residence along the Bosphorus in the Beşiktaş area, and the British military hospital at Scutari (now Üsküdar) used during the Crimean war and where Florence Nightingale gained fame.

(1857 map of the British consular buildings at Constantinople)

Even so, enough buildings and structures present in 1859 remain, and they provided me with a better sense of the geography, architecture, and atmosphere of important moments and themes in the story.

(Sublime Porte—the gate that British diplomats entered to meet with Ottoman officials, under restoration)

(Old British Embassy, now the British Consulate General)

All fiction involves sustained acts of imagination. Historical fiction embeds imagination in specific time-bound contexts that challenge authors to mesh authenticity and creativity. Done well, the weaving produces something beautiful and gossamer. The difficulty of that task is why, not having visited Istanbul before finishing the novel, I worried that I lacked something critical concerning authenticity and creativity.

(Dolmabahçe Palace)

When I encountered key buildings or locations in my novel, I found myself reenacting, mentally or physically, the fictional scenes in their real settings. Those reenactments helped me sense that the balance I struck between authenticity and creativity was rough-and-ready enough to advance the plot and support character development. Rough-and-ready is a low bar, but writing historical fiction involves eating humble pie. Even so, being in Istanbul with my characters and story generated insights about how to better manage the challenges that historical fiction authors face that I can, hopefully, apply in my works-in-progress.

(Turban-topped headstone in a graveyard (Süleymaniye Mosque))

Why I Wrote the Novel

Writers of historical fiction also confront the challenges of how to make history interesting to contemporary readers (entertainment) and relevant to current political and social affairs (engagement).

I focused on one of the most important and controversial features of international politics in the nineteenth century—the application of the so-called “standard of civilization” by the European powers (e.g., Britain) against non-European nations (e.g., the Ottoman empire).

The story is set within that geopolitical clash of civilizations. It also Includes political clashes happening within each competing civilization (e.g., power v. justice; tradition v. modernization). The consequences of the imposition of the standard of civilization in the nineteenth century continue to reverberate in today’s world.

Exploring Istanbul provided tangible examples of the shock waves that the standard of civilization caused. I toured both the Topkapi Palace, located in the Old City, and the Dolmabahçe Palace, built next to the Bosphorus on the European side of the strait. Topkapi was the primary palace for Ottoman sultans from the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 until 1856, when Dolmabahçe became the main palace.

The architecture and decor of Topkapi are decidedly Asian and reminded me of what I saw traveling through famous Silk Road cities in central Asia, such as Bukhara, Khiva, and Samarkand. In contrast, Dolmabahçe is thoroughly European in design and decoration.

I did not include Topkapi in the novel, but my visit to Istanbul suggested that I could have exploited the contrasts between it and Dolmabahçe in service of the story’s themes. The differences between the palaces are a physical manifestation of the pressure that the Ottoman empire was under in the nineteenth century to Europeanize in order to be considered civilized.

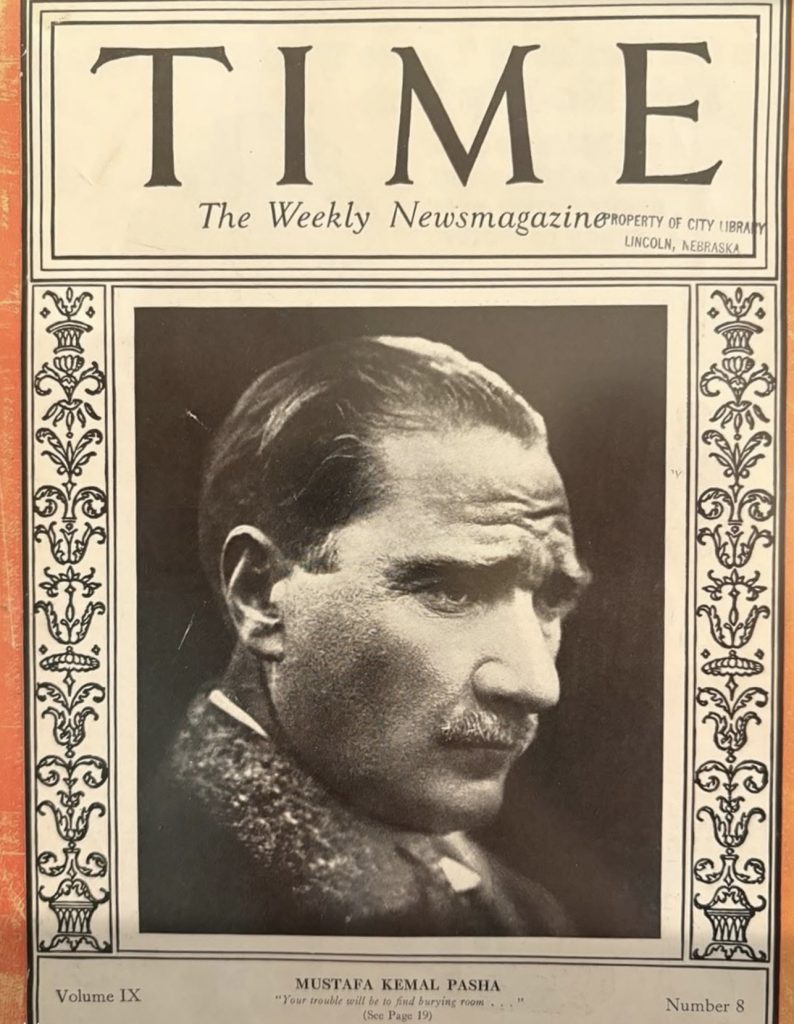

The demand, need, and desire to modernize on European models are also manifest in how Istanbul continues to honor the founder of the secular Turkish republic, Kemal Ataturk. Ataturk’s role in history began after the time of my novel, but I included one small scene to hint at his emergence as the most important post-Ottoman leader of the Turkish people.

(Time Magazine on Kemal Ataturk (1927), displayed in the Dolmabahçe Palace)

However, Turkey’s current president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, is pursuing policy agendas that draw on the Ottoman past. That approach involves elevating the role of Islam, such as making Hagia Sophia a mosque again and building the massive Çamlıca mosque on the Asian side of the Bosphorus. Erdoğan’s policies also reflect so-called “neo-Ottomanism,” defined by one commentator as the “strategic and ideological framework in which Turkey seeks to extend its economic, political and cultural influence across regions historically under Ottoman control, including the Middle East, North Africa and the Balkans.” I am no expert on Turkish politics, but Istanbul contains signs that Erdoğan is challenging Ataturk’s legacy.

(Hagia Sophia)

The Ottoman struggle in the nineteenth century to grapple with the change caused by surging European power and the standard of civilization is a central theme in my novel. Among leaders and within the population, no consensus existed on how and why to change—apart from conceding that the Ottomans could not avoid transformation. My main Ottoman character, Mehmed, attempts to find a principled, pragmatic way to guide reform only to be harassed and thwarted at every turn.

The challenge of recalibrating politics to economic, social, and technological change is not, of course, unique to the Ottoman empire and contemporary Turkey. Western democracies—many of which which were the European powers that imposed the standard of civilization in the nineteenth century—are embroiled in domestic and international political controversies that feature the fault lines running through the historical events and conceptual themes in A Court at Constantinople.

Conversations that I had in Istanbul suggest that today’s so-called decline of the West echoes the collapse of the standard of civilization in the early twentieth century after World War I. That inflection point triggered turmoil about how governments in every region of the world calibrated power and justice in balancing tradition and reform in responding to change. As happened between the first and second world wars, authoritarianism is now increasing globally, led by revanchist states (e.g., China and Russia) seeking to change the international system in their favor, while the United States steps back from international leadership.

In that sense, Istanbul, like Byzantium and Constantinople before it, reflects—and affects— trends and forces reshaping domestic and international politics around the world. Those churning dynamics challenge people exercising power—and individuals simply finding their way in a world that too often will just not let them be. Those dynamics are at the heart of historical fiction, even the rough-and-ready kind.