Writers of historical fiction often use archival material to enhance a story’s authenticity and to create characters and plot. My research for A Court at Constantinople included visiting the UK National Archives to read correspondence between the Foreign Office in London and Her Britannic Majesty’s Supreme Consular Court at Constantinople from 1857–the year the court was established–until approximately 1865.

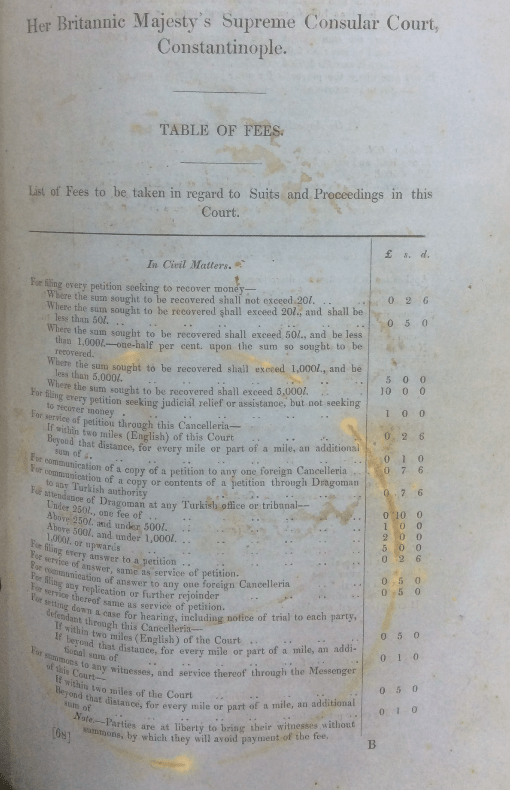

I ferreted through mundane, fascinating, and perplexing exchanges between Constantinople and London contained in printed documents, formal despatches, scribbled notes, and letters about matters before the court. In a time now dominated by the digital and virtual, handling these old papers felt visceral. Traces of the hands through which they passed were ubiquitous–stray ink drops, idiosyncrasies of penmanship, curious marginal notes, faint pencil lines for turning rough drafts into final communiques, a paint-can ring staining an official document.

I remember writing drafts longhand and plunking them into completed papers on non-electric typewriters. But, even with my experience of pre-digital writing, the physical effort it took to produce the materials in the archive was striking. The volume and variety of handwritten documents, the numerous drafts, the editing, and the final versions represented a disciplined, deliberative, and formal enterprise that consumed considerable time, thought, and energy on a daily basis.

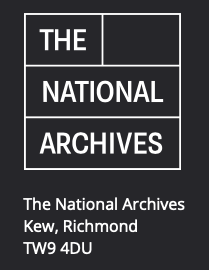

In the case of the British Supreme Consular Court at Constantinople, much of the back-and-forth with the Foreign Office dealt with weighty matters of law, justice, and power politics. Her Majesty’s Government established the court to reform how the British consular system in the Levant engaged in judicial matters. The Foreign Office intended these reforms to serve as examples for the changes that the British believed the Ottoman government needed to make to its laws and court system. But amidst such high diplomacy arose more down-to-earth problems that Edmund Hornby, chief judge of the court, and his colleagues had to manage.

In a December 1857 despatch to the Foreign Secretary, Judge Hornby reported on the lack of clean water for the consulate court and prison buildings and his plan to collect rain water to remedy the problem. The water issue threatened Hornby’s efforts to improve sanitation and other conditions at the consular gaol. But making the gaol safer and healthier for prisoners encouraged behavior that created a different challenge.

In the same despatch, Hornby complained that the prison was housing too many people. He unpacked the incentives that prompted British sailors arriving at Constantinople to commit petty offenses that put them in gaol for a short spell. These sailors avoided physical labor and the discomfort of living on the docked ship, and ship masters saved money by paying lower wages for local workers to complete tasks. Confronted by this “law and economics” problem, Hornby proposed using fines rather than imprisonment to reduce the gaol’s population.

As interesting as they are, the archival materials provided a limited perspective on the diplomatic issues and the personalities involved. Judge Hornby is the main British “character,” and his intellect, temper, and resilience are on display across the documents. But the archives do not illuminate his Ottoman counterparts. Indeed, one Ottoman official with whom Hornby tussled was, in fact, British—Sir Aldolphus Slade, a former Royal Navy admiral employed by the Ottoman government. Hornby and Slade did not get along. The Foreign Office reprimanded Hornby for quarreling with Slade, who wrote letters about the judge’s animosity.

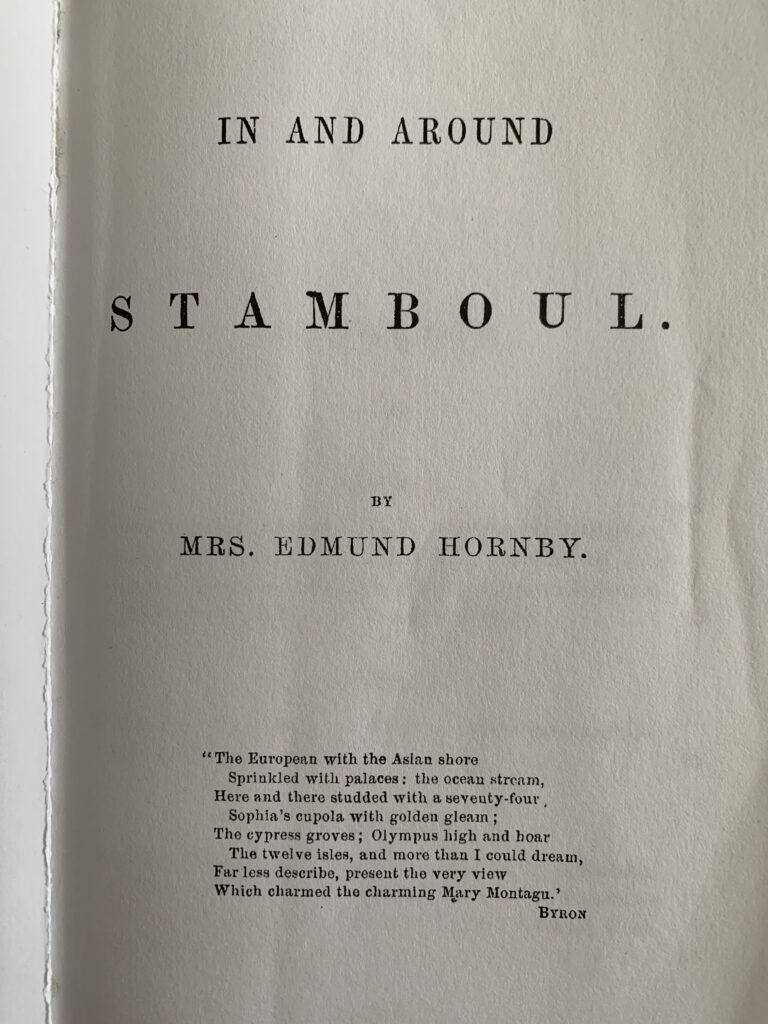

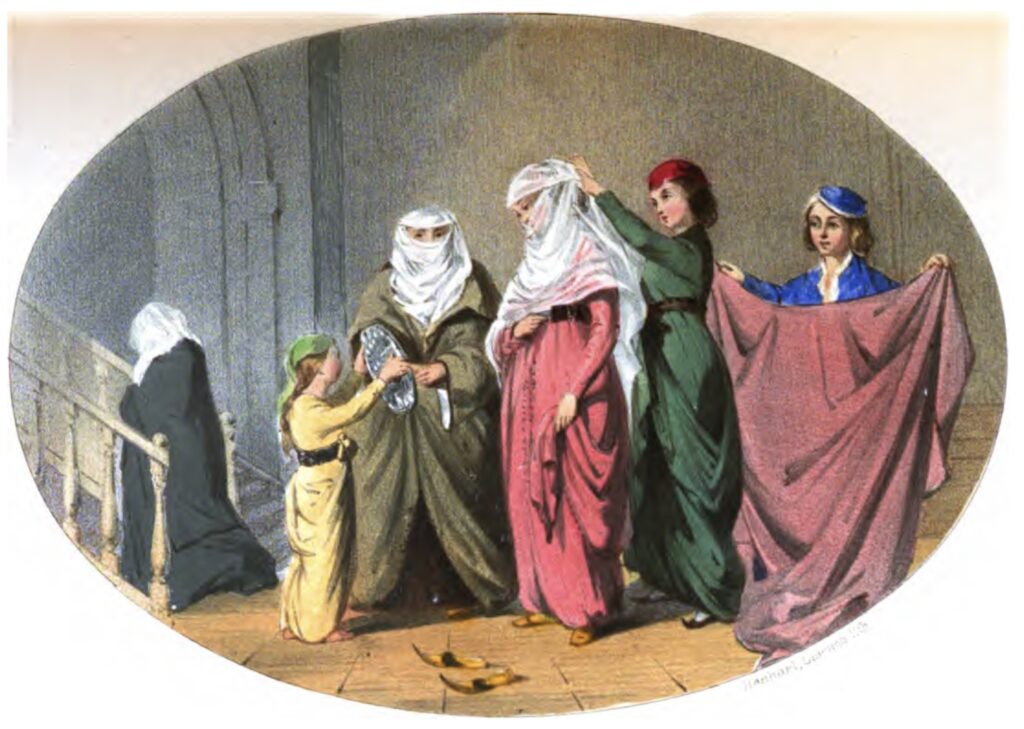

The archives were also a man’s world. The consular court handled family law matters among Her Majesty’s subjects living in Ottoman lands, but the diplomatic correspondence did not touch on gender relations in British law and society. Nor did the archives provide enlightenment on the place of women in Islamic and Ottoman jurisprudence. As luck would have it, Judge Hornby’s wife, Emelia, published a memoir in 1858 of her time in Constantinople during the Crimean war when Edmund held a different post. The memoir provided Emelia’s contemporaneous “archive” on things found nowhere in the documents flowing between London and Constantinople.

In seeking authenticity and creativity from archives, writers of historical fiction grapple with how much elasticity should exist between these objectives. Being able to find an effective equipoise between fact and fiction is a hard-earned craft. In my experience, developing and honing this craft produces its own archive of materials—countless drafts, stacks of documents, misplaced notes, endless tracked changes, confusing marginalia, sobering emails, proliferating digital folders, piles of empty printer cartridges, and coffee-mug rings staining chapters naively believed ready for the world to read.