Of late, mainstream and social media have been awash with the wonders of, and worries about, developments in artificial intelligence (AI). Innovations—such as ChatGPT, its iterations, and its competitors—appear to herald the promise of more sophisticated AI. This burst of attention has come with infectious excitement about the potential of AI technologies and with proliferating concerns about the threat that AI poses to human creativity.

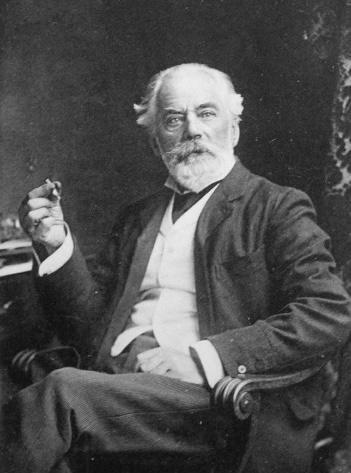

In watching debates about these next-generation AI programs, I—like others—succumbed to the temptation to take a test drive. I queried AI software that generates facial images to get “portraits” of Sir Edmund Hornby, a British barrister knighted for his service as a consular judge in Her Majesty’s Service in the Ottoman empire, China, and Japan. Hornby is an important character in my novel A Court at Constantinople. In my research, I found only one photograph of Hornby, probably taken around 1884, more than two decades after the year—1859–in which my novel unfolds.

In 1859, Hornby was the chief judge of the British Supreme Consular Court at Constantinople and was in his mid-30s. I provided two AI image-generators with the same general information and specific details, which they ran through their respective algorithms. The resulting portraits are, fittingly, very different.

Instigating the AI-creation of these images was an amusing way to procrastinate, but the outcomes made me look harder at what emerged. Neither matched what was in my “mind’s eye” for Edmund Hornby in my novel. Each made me realize how unspecific—or perhaps how generic—my imagination had been about the face of an important character in my story. Was I, the human writer, just schooled by AI to be more creative?

This little experiment made me uneasy for another reason. AI is a powerful technology that continues to spawn political and ethical concerns that policymakers struggle to comprehend, let alone address. The scale of the potential manipulation of increasingly capable AI software for malevolent purposes is alarming when societies already struggle with the negative consequences of their deep dependence on digital technologies.

Interestingly, these concerns brought me back to Edmund Hornby and his colleagues at Constantinople. The expansion of British influence into the Ottoman Empire and Levant region in the 1850s was fueled by, among other things, waves of technological innovation. The Industrial Revolution was altering how economies produced goods. Steamships and railroads were transforming transportation within and among nations. The telegraph radically changed communications in ways that led a historian to call it the “Victorian internet.”

These innovations changed the context and nature of diplomacy, as Hornby and others in Her Majesty’s Service discovered. As G. R. Berridge wrote in British Diplomacy in Turkey:

“[A]t least in the decade after 1856, the Foreign Office appears to have had a greater volume of correspondence with the embassy at Constantinople than with any other diplomatic mission. It is therefore not surprising that the introduction of the electric telegraph in the middle of the century, which dramatically quickened the speed with which messages might be exchanged, was of particular interest to this post. Messages that until recently had taken weeks to reach London could now get there in about 24 hours.”

The telegraph brought not only a faster way to communicate but also concerns familiar to users of digital technologies in the internet era—misinformation, disinformation, disrupted access, insecure communications, and espionage. I used these historical parallels in the novel. Judge Hornby engages in “telegraphic legal research” during an important criminal trial and confronts problems associated with the speed of telegraph messages, leading him to declare in exasperation, “This telegraph, it spreads contagion with no chance of quarantine.”

That complaint could, of course, be applied to digital communications facilitated by the internet, particularly social media. My uneasiness with AI-generation of facial images is rooted in the way digital technologies have—as the telegraph did in the Victorian age—created more challenges than they have resolved. I had a bit of fun, but I’ve been around cyberspace long enough to worry that, at the moment, we have no means to quarantine the problems that ever-more powerful AI technologies will bring.