My novel, A Court at Constantinople, was published on March 29 and, thus, became fair game for book reviewers. The first review I saw was thoughtful and rendered with care, awarding the novel four out of five stars. I wanted more of the same, but I quickly ran across a cluster of reviews that made me smile and scowl in swift succession.

These reviews did not trash my novel and, by and large, praised it. My mirth arose because artificial-intelligence chatbots—activated by people who read neither the book nor its short marketing blurb—wrote wildly nonsensical reviews of the novel.

However, my amusement rapidly turned into consternation because, no matter how primitive as examples of chatbot capabilities, these reviews serve as a harbinger and warning for the disruptive impact that artificial intelligence might have on the industry of writing and reviewing novels.

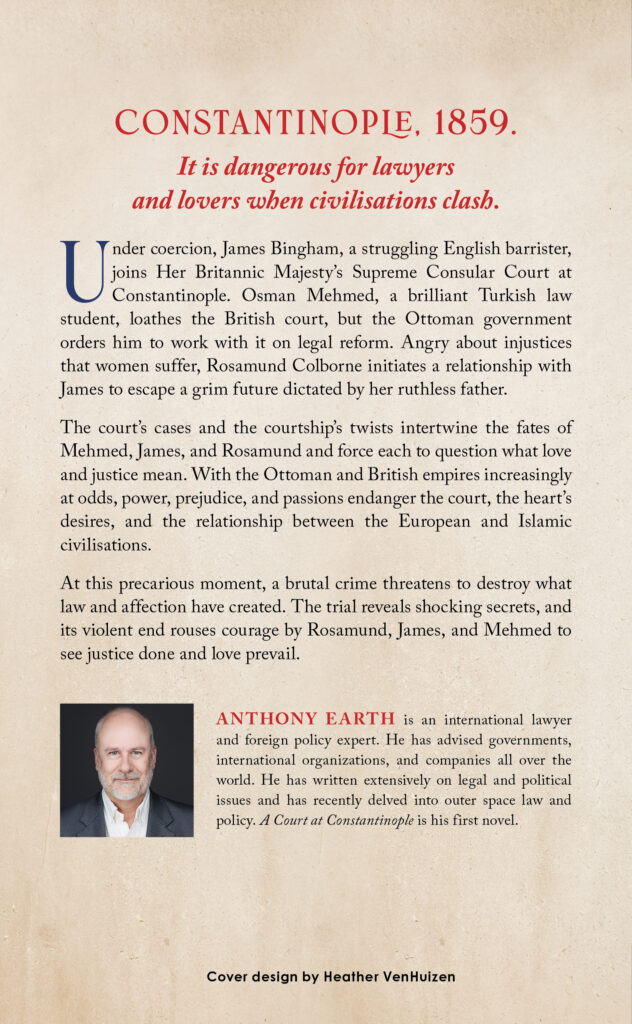

Let me highlight why the binary fingerprints of chatbots are all over these reviews. But first, please digest these opening lines from the novel’s blurb that identify the time period and the main characters:

“Constantinople, 1859. It is dangerous for lawyers and lovers when civilisations clash.

A Court at Constantinople

Under coercion, James Bingham, a struggling English barrister, joins Her Britannic Majesty’s Supreme Consular Court at Constantinople. Osman Mehmed, a brilliant Turkish law student, loathes the British court, but the Ottoman government orders him to work with it on legal reform. Angry about injustices that women suffer, Rosamund Colborne initiates a relationship with James to escape a grim future dictated by her ruthless father.”

The first review that I read in the problematic cluster raised an eyebrow by stating that the novel provides a “fascinating historical account of the tumultuous times” of “the enigmatic Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1876 to 1909.“ The review only gave me three stars, perhaps because my novel was set nearly twenty years earlier when a different sultan, Abdul Mejid I, reigned. But at least the review stayed in the correct century. Things get worse—and weirder—with the rest of these reviews.

Magnificent, by Titian

The next one described a “gripping historical novel set in the 16th century Ottoman Empire” that “follows the story of Nicholas, a young Venetian merchant at the court of the grand Sultan his [sic] Suleiman.” We have moved from the nineteenth century to the sixteenth century with a different sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent (who reigned from 1520 until 1566), and a Venetian man of commerce as the protagonist. But, to be historically pedantic as well as gripping, shouldn’t the merchant of Venice be named Niccolò?

The next review praised my “painstakingly researched and gripping historical fiction book . . . set in the Ottoman Empire in the latter half of the sixteenth century” in which “the plot centres on Thomas Dallam, an English organ manufacturer who was sent to Ottoman Sultan Murad III as a gift by Queen Elizabeth I.” Was Queen Elizabeth in the habit of giving organ makers as gifts to foreign rulers?

The final two reviews both had the novel set in the Byzantine empire during the tenth century—ages before the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453. One states that the novel “follows the story of John, a young man who dreams of becoming a member of the emperor’s court.” The other describes the story as focused on “Basileios, a young nobleman who is granted the chance to work as a secretary at the imperial court.” In either of these novels, do the ambitious John and the lucky Basileios cross paths in the emperor’s court?

Each review in the cluster opens with a sentence summarizing the novel. The one that gave the game away was effusive about an “authentic novel that skillfully investigates the complexities of the Footrest Realm.” The poor chatbot was confused by the difference between one of history’s great empires and something on which people rest their weary feet at day’s end.

by Santi di Tito

This laugh-out-loud line connects with other moments when the chatbot penny drops in reading the reviews. Perhaps the chatbot picked up that Niccolò Machiavelli wrote his famous book, The Prince, in 1513–just before Suleiman became sultan–and had positive things to say about the nature of Ottoman rule. (OK, Machiavelli was Florentine not Venetian, but it is historical fiction.) Thomas Dallam was a real person who travelled from London to Constantinople in 1599 to build an organ that Queen Elizabeth sent to Sultan Mehmed III as a gift. Basileios could have been bot-scraped from websites about Basileios the Macedonian, or Basil I, emperor of the Byzantine empire in the ninth century. Born into peasantry, Basileios made his way into the imperial court at Constantinople and eventually became emperor in 867. I have no clue on what historical figure John—the young man seeking to join the imperial Byzantine court—might directly or remotely be based.

The presence in cyberspace of possible historical material for Nicholas, Thomas, Basileios, and—maybe—John does not, of course, explain why reviews of a book set in 1859 with protagonists named James, Mehmed, and Rosamund described tales anchored in other time periods about earlier and later Ottoman sultans, a Venetian merchant, an English organ maker, an upwardly mobile young man in Byzantium, and a Byzantine nobleman. Answering this mystery requires knowing how the persons responsible for these reviews interacted with chatbots—an avenue of inquiry unlikely to succeed.

For me, this experience hints at how disruptive artificial intelligence might be for the Novel Writing Industrial Complex. Whatever happened with the chatbot reviews of my novel was quite crude, quickly spotted, and easily called out. However, as is apparent from increased handwringing about the impact of artificial intelligence on writing and other creative arts, the rudimentary nature of current AI software will improve, become more sophisticated, and blur the lines between human cleverness and machine learning. The Footrest Realm will not last forever. Chatbot written novels and book reviews are coming, and we are not ready.

[…] But, this world of nonfiction is beholden to facts, bounded by professional disciplines, and based on shared analytical projects. In publishing my novel, A Court at Constantinople, I wondered whether the scar tissue and callouses earned in professional endeavors would help me absorb and learn from reviews of the completed novel. Or, more precisely, reviews by humans rather than chatbots (see Earth/Note 6: Gripping Tales from the Footrest Realm). […]