In A Court at Constantinople, English barrister James Bingham arrives in Constantinople in January 1859 and receives a letter from Carlton Cumberbatch, the British Consul General, welcoming him to Her Majesty’s Service. Otherwise, Carlton plays no role in the story. Even so, I wondered whether Consul General Cumberbatch was a relative of the British actor, Benedict Cumberbatch. I never pursued the question because it was idle curiosity and the answer to the question was not important for the novel.

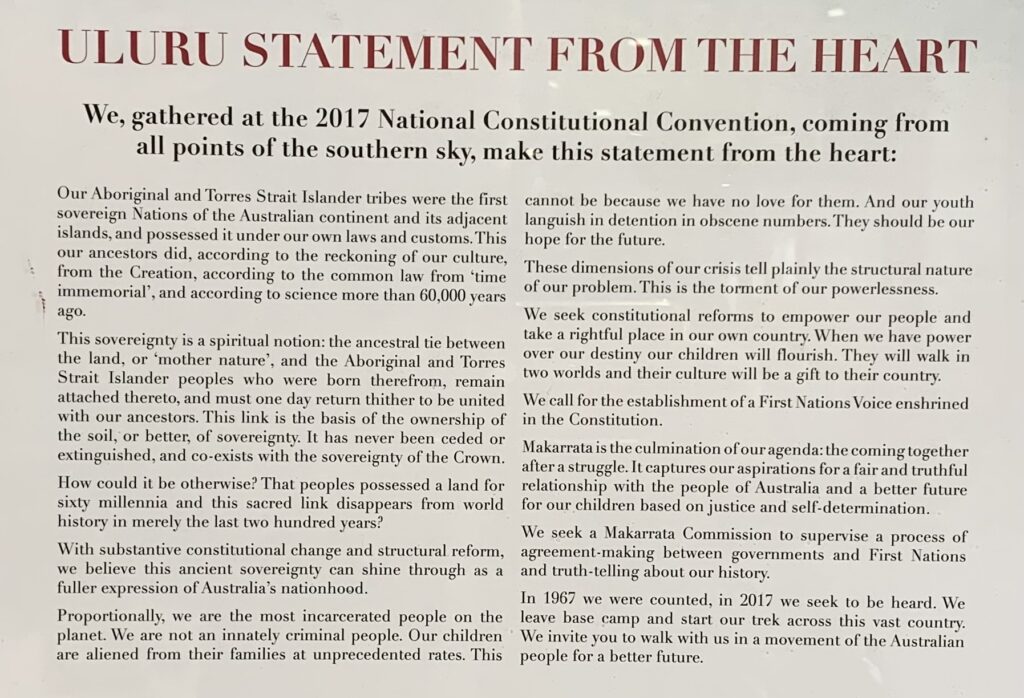

But then, when I was in Australia earlier this month, controversies surfaced in the Australian press about paying reparations to aboriginal peoples dispossessed, discriminated against, and otherwise harmed by British colonization. These controversies arose in connection with a proposal for a constitutional amendment to give aboriginal peoples a stronger voice in Australian politics. The referendum on “The Voice” proposal takes place later this year. The foundational document for this movement is the Uluru Statement from the Heart adopted by aboriginal leaders in 2017.

Being only somewhat aware of the mistreatment of Australia’s aboriginal people since the British arrived in 1788, I did some research to understand the past as well as present-day Australian politics on the proposed constitutional amendment. To my surprise, my googling surfaced Australian news stories about whether Benedict Cumberbatch should pay reparations to the people of Barbados because his ancestors—starting with Abraham Cumberbatch in the 1700s—had owned slaves on a plantation there until Britain abolished slavery in the 1800s.

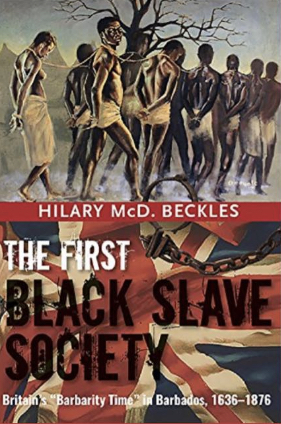

Slavery in Barbados was particularly brutal. Barbadian scholar Hilary Beckles argued in The First Black Slave Society (2016) that the country “was the birthplace of British slave society and was the most ruthlessly colonized” because it “was ideally suited to sugar plantations” that made fortunes for “British royalty and ruling elites” that “secured Britain’s place as an imperial superpower.”

This history explains, in part, why—as Time Magazine addressed in a July 6, 2023, article—Barbados has been a leader in the international movement for the payment of slavery reparations.

Although not about “The Voice” referendum in Australia, the connection between Benedict Cumberbatch and demands for slavery reparations in Barbados made my curiosity about Carlton Cumberbatch less idle. Some admittedly unsophisticated genealogical digging indicated that Benedict and Carlton are related.

By 1859, Britain had abolished slavery and the slave trade within its dominions and was engaged in bringing the international slave trade to an end. Carlton, as head of the British consulate in Constantinople since 1845, was likely involved in diplomatic efforts to end the slave trade in and around the Ottoman empire. As Slavery in the Ottoman Empire and Its Demise, 1800-1909 (1996) noted, most “measures against the slave trade by the Ottoman government were taken as a result of British diplomatic initiative,” including the “general prohibition of the black slave trade in 1857.”

Thus, from slave-owner Abraham to diplomat Carlton, Benedict Cumberbatch’s ancestors were involved in some of the worst and best aspects of Britain’s exercise of imperial power. That family history reflects what Nigel Biggar argues in Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (2023) is a more complicated political and ethical context for the British empire’s relationship with slavery than many of its critics acknowledge.

Interestingly, Benedict’s career has involved roles that connect to the best and worst of the West’s involvement with slavery. In Amazing Grace (2006), he played Prime Minister William Pitt, who supported William Wilberforce’s movement to abolish Britain’s participation in the slave trade. In 12 Years a Slave (2013), he portrayed a slave owner in the United States before the Civil War. Press reports indicate that Benedict’s motivation for taking those roles included his awareness that some of his ancestors had engaged in the slave trade and slavery.

For my novel, connecting Consul General Carlton with the actor Benedict provides a bit of trivia. But making that connection also touches serious and controversial issues about the legacy of imperialism, which includes demands for slavery reparations—as Barbados is making—and for a greater political voice for indigenous peoples, as proposed in Australia.

What happens with such demands and proposals remains to be seen. Barbados has made it clear that it is not targeting Benedict Cumberbatch in its slavery reparations campaign. When I left Australia in early July, the media was reporting that polling indicated that the referendum on “The Voice” constitutional amendment would fail when held later this year.

These two contemporary undertakings reflect what historical fiction communicates—the present never escapes reckoning with the past.