Historical fiction typically features real persons as characters in tales set in yesteryear. Those tales usually do not encompass the lifespan of such persons, whose lives often touched history before or after the fictional stories begin and end.

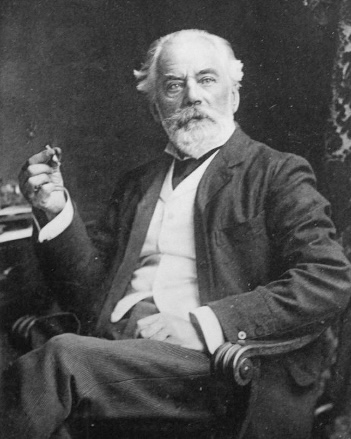

One major character in my novel, Edmund Hornby—an English barrister in the British diplomatic service—was such a historical figure. Under orders from Her Majesty’s Government, Hornby established the British Supreme Consular Court at Constantinople in 1857 and served as its chief judge until the Government sent him to China to create and oversee a similar tribunal. My historical tale centers on the court at Constantinople and its impact on British subjects living in the Ottoman empire and on Ottomans interacting with British diplomats, merchants, and missionaries at a transformative time in world affairs.

Hornby’s involvement with global events did not cease after he left Her Majesty’s Service in the 1870s. He was also active in the last decades of the nineteenth century in projects to establish an international court to resolve disputes among nations.

That part of Hornby’s story came back to life for me because the International Court of Justice has been much in the news recently concerning a case in which South Africa has accused Israel of committing genocide against the Palestinian people during the Israeli military campaign against Hamas in Gaza.

From a British to a World Court

With other lawyers and peace advocates, Hornby contributed to efforts to create an international court or tribunal that could help countries resolve disputes and avoid war. Proposals for such a judicial body predated the nineteenth century, but the push for a permanent international court in the latter half of that century informed international tribunals created in the twentieth century, such as the Permanent Court of International Justice established after World War I and the International Court of Justice constituted after World War II.

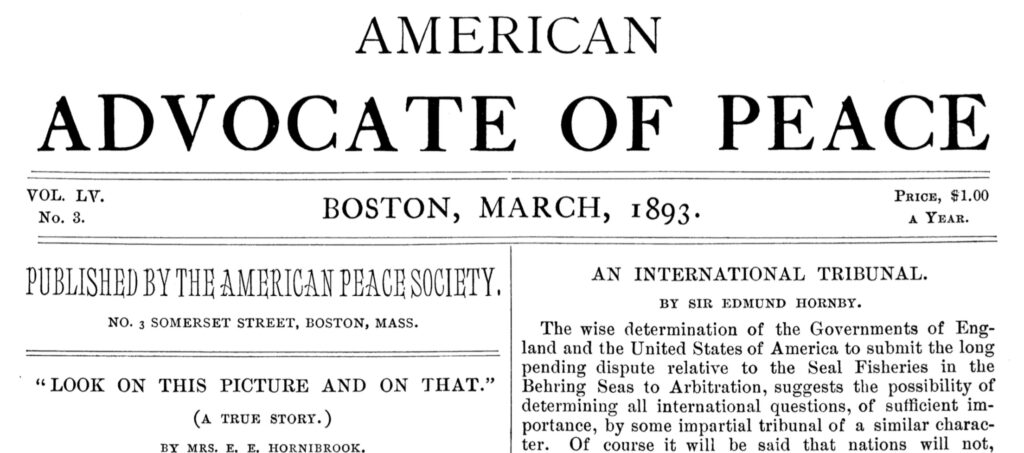

In March 1914, the Yale Law Journal published “Proposals for an International Court,” which included Hornby’s plan for an international tribunal alongside the ideas of philosophical and international legal luminaries, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jeremy Bentham, David Dudley Field, and James Lorimer. Hornby laid out his proposal in an article entitled “An International Tribunal” published in the early 1890s in the London Herald of Peace and, later, the American Advocate of Peace by groups involved in the international peace movement.

Hornby justified his proposal on arguments that war between nations had become politically, economically, and morally unjustified. The time had arrived, he believed, for establishing a permanent international court to settle disputes by legal rather than military means. In addition, Hornby thought the operation of such a court could help develop the system of international law that remained, in his opinion, incomplete—a state of affairs that provided nations with incentives to rely on power rather than justice in resolving disputes.

For me as an international lawyer, Hornby’s proposal brims with interesting details that reflect major themes in thinking about war and peace prevalent in the decades immediately before World War I. As a writer of historical fiction, I see parallels between how Hornby established the British Supreme Consular Court at Constantinople and his plan for an international court.

Before Hornby arrived in Constantinople in 1857, the legal component of the British consular system in the Ottoman empire operated in arbitrary and abusive ways, which created unjust outcomes for British subjects and constant friction between the British and Ottoman governments. Hornby radically changed the judicial functions of the British consular service in Ottoman domains by reorganizing the consular courts and adopting a detailed legal code to ensure that each consular court settled disputes under the same rules.

In short, Hornby created new judicial institutions and processes that could develop the rule of law for authoritative, transparent, and just settlement of disputes—essentially the formula he used in his proposal for a permanent international court. He—and other British diplomats—argued that the new British consular court system could serve as an example for legal reform in the Ottoman empire and other non-European nations. Hornby—and other advocates for an international court—believed that such a court could support more peaceful relations among developed and less-developed countries.

A World Court in a World at War

Hornby’s actions in Her Majesty’s Service and his ideas for an international court were products of his era, which World War I (1914-18) effectively ended. That tragedy destroyed European justifications for operating consular courts, such as the one Hornby built at Constantinople, in non-European countries. The catastrophe buried pre-1914 arguments that war had become too politically, economically, and morally costly for states to pursue.

In the wake of the conflict, states established the Permanent Court of International Justice, fulfilling the long-held dream for such a judicial body. That court, however, did not prevent World War II (1939-45), a global conflagration more bloody and destructive than the great war just over twenty years earlier. Similarly, created in 1946, the International Court of Justice (ICJ)—often called the World Court—did not deter states from threatening or waging war to achieve political objectives in the Cold War era.

South Africa’s claim at that ICJ that Israel’s military campaign against Hamas in Gaza has violated the Genocide Convention—and the intense controversies the case has generated—appears as experts observe that, again, we have a “world at war.” That state of affairs includes armed conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, with the threat of war increasing in the Asia-Pacific region in connection with China’s claims of sovereignty over Taiwan, border regions with India, and the South China Sea.

A world at war diminishes the World Court’s impact and calls into question how much international law has developed across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Put differently, Hornby’s primary objectives in advocating for a permanent international court to counter war—demonstrating the importance of such a tribunal and advancing the system of international law—have not been achieved. Indeed, some commentators are exploring whether today’s increasingly violent world exhibits features present in international relations in the years before the outbreak of World War II.

War and Genocide, Power and Justice

The South Africa v. Israel genocide case will continue after—perhaps years beyond—the ICJ’s January 2024 decision on provisional measures. Whether the ICJ ultimately rules that Israel violated the Genocide Convention remains to be seen. What is clear is that the ICJ’s proceedings on the case will not settle controversies about international law on genocide, end the war in Gaza, or resolve armed conflicts underway or looming elsewhere in the world. Today, the optimism about law and courts that Hornby exhibited during his time as a British diplomat and in his advocacy for an international court proves difficult to develop and sustain.

The challenges to peace and order that countries now face reignite old questions about whether justice is possible in relations between sovereign states. Toward the end of my novel, Hornby worries about the Foreign Office’s desire for him to take the judicial and legal strategy implemented across Britain’s consulates in the Ottoman empire and apply it to the British consular service in the Far East. He asks himself whether his ideas about law and justice merely reflect the ancient adage from Thucydides that “the strong do what they can, while the weak suffer what they must.”

The evergreen nature of that question challenges diplomacy and international law—and makes fertile material for historical fiction.