The Nonfiction School of Hard Knocks

As an international lawyer, my professional work typically runs a gauntlet of comment and criticism before seeing the light of day. Critiques, of course, continue after daylight, but it is the earlier review process that produces a thick skin that absorbs the sticks and stones of scrutiny and opens opportunities to admit mistakes, see new perspectives, appreciate smart editing, think more deeply, and write more persuasively. With a thick enough skin, learning can even happen while pondering petty stones peevishly cast.

But, this world of nonfiction is beholden to facts, bounded by professional disciplines, and based on shared analytical projects. In publishing my novel, A Court at Constantinople, I wondered whether the scar tissue and callouses earned in professional endeavors would help me absorb and learn from reviews of the completed novel. Or, more precisely, reviews by humans rather than chatbots (see Earth/Note 6: Gripping Tales from the Footrest Realm).

As reviews and other feedback on the novel trickled in, the thick skin was not proving particularly helpful. The common framework that supported learning in the nonfiction school of hard knocks was missing. Instead, the author’s freedom to create met the reader’s equal and opposite liberty to react. This dynamic produced, for me, a disorienting terra nova for which I had no compass.

And Now for Something Completely Different

That expert review of nonfiction and reader responses to fiction would differ was, in theory, no surprise. “Art is in the eye of the beholder,” and all that. I have gazed upon museum masterpieces or plowed through famous novels and–even with a degree in English literature–sometimes just didn’t “get it.” Such shoulder shrugging would often make me dive into expert expositions to learn about the greatness my eyes could not behold unaided. Nonfiction remained a center of gravity for me in the world of the imagination.

However, this center could not hold when I wrote a novel that others read and reviewed. As a nobody writing fiction in the world of fiction, I am more a cliche than an artiste. My ego–much more invested in a remunerated profession–shrugged its shoulders when reviewers tipped their hats or wagged their fingers about the novel. Thick skin, and all that.

But I was lost in terms of how to learn from readers’ reactions, especially positive and negative reactions I didn’t “get.” And, if I can’t learn from what went well and badly for readers with this novel, how will my next attempt at sustained imagination be, even incrementally, better? My discombobulation arose, in part, from being a fiction neophyte without the experience, confidence, and sensibility to read the tea leaves in reviews. But humble pie is junk food when the hunger arises from intrinsic and analytical motivations.

All Over the Map

My confusion about how to learn from reviews had a more direct source–reader reactions have, so far, exhibited diversity. Those who liked the novel expressed different reasons–the themes it explored, the thrilling and suspenseful pace, the richly drawn characters, and the historical authenticity. Those less impressed also identified a multiplicity of rationales–dull or annoying characters, dragging pace, pretentious vocabulary, and too much legal stuff.

Attempts to find patterns across and within positive and negative reviews provided little traction. Clusters in the “tip of the hat” category (e.g., rich characters, historical authenticity) had opposite “wag of the finger” reactions (e.g., dull characters, too much legal stuff). Reasons also varied within the categories, such that, for example, dislike of the legal material was not a common complaint. I also found no indication that responses tended positive or negative whether the reviewer read the novel or listened to the audiobook.

No Time to Lawyer Up

In the absence of patterns, I succumbed to the unhelpful desire to “argue” with reviewer comments, including positive feedback that made me scratch my head. Lawyering up to engage in analytical knife fights, like those nonfiction reviews often produce, has not been constructive for absorbing what reviews of the novel communicated about the reader’s perspective and preferences.

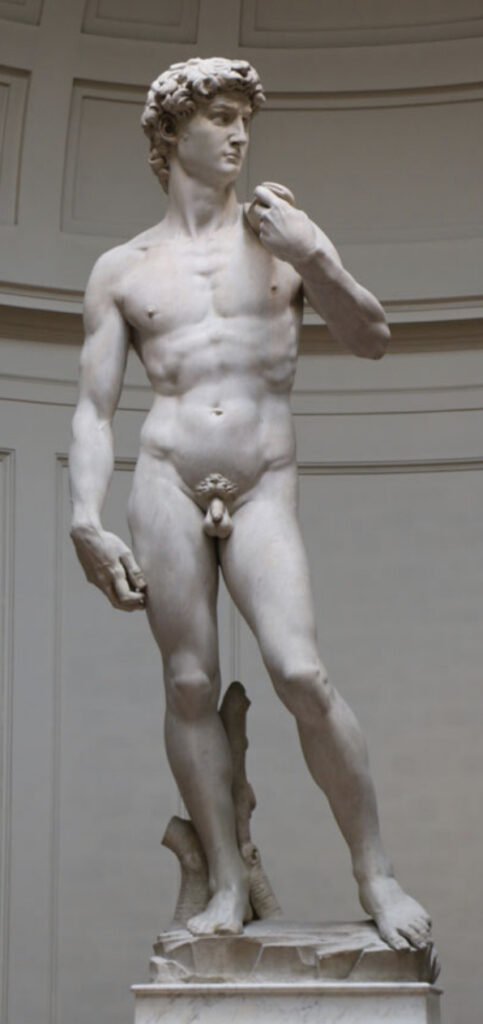

Joshua Reynolds, circa 1769

This unfortunate impulse reminded me of something Edmund Burke, the great eighteenth-century British statesman and political thinker, said about the legal profession. Burke studied to become a lawyer, but he abandoned the effort because he felt his legal training lacked the liberality of mind necessary to understand justice in human affairs.

Burke, of course, wasn’t talking about novels. But his sentiment about the liberality of mind applies to the world of fiction. Authors create; readers deliberate. Both are liberated to think and communicate unbound by the strictures of facts, professional disciplines, or analytical objectives. This context is one in which “learning” will be different for author and reader.

Still Time to be Schooled

It is still early days; more reviews might arrive for my edification. Perhaps I will, with time, be able to do justice to how authors and readers imagine the fictional worlds where they meet.